Toasting Casks

Published 8 Aug 2022

I have previously explored how seasoning wood prepares it for use in spirit casks. Seasoning is a long, slow process that reduces ellagitannins, hydrolyses bitter coumarins and increases aroma compounds due to degradation of wood macromolecules by microflora. Seasoning is usually followed by toasting, which by contrast is a much faster process dramatically altering the chemistry of the wood. Toasting normal occurs as the cooper assembles the cask, as the heat inside the cask helps bend the staves into shape.

A lightly toasted cask spends about 25 minutes exposed to heat while a heavily toasted cask may get up to one hour of heat exposure. During toasting the wood is brought to a temperature between 150-240° Celsius. There are two phases: in the drying phase water is forced out of the wood, in the toasting phase there are complex thermal degradation reactions that derive aromatic volatile compounds from non-volatile precursors. In general terms the derived flavour compounds in the wood increase dramatically with toasting, but the amount of flavour compounds is affected by two main factors: the toasting temperature and the length of time. The important flavour compounds derived during toasting are derived from lignin, polysaccharides (cellulose and hemicellulose) and lipids. Flavour compounds are also destroyed during toasting, most notably tannins.

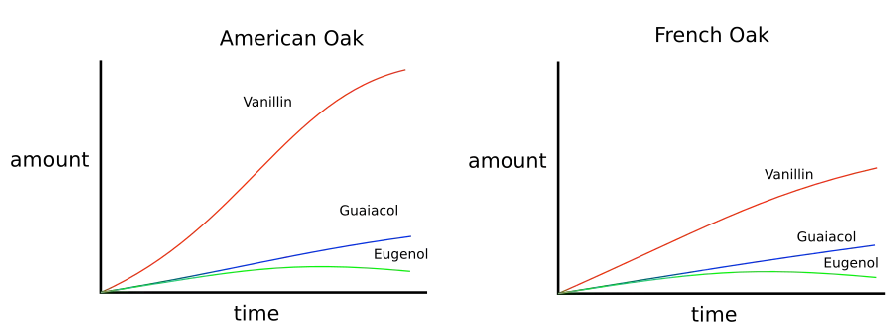

The flavour compounds vanillin, guaiacol and eugenol are derived from lignin during toasting. Vanillin imparts a vanilla flavour whilst guaiacol imparts a smokey flavour. Eugenol gives a clove like scent. Lignin is generally considered the most stable wood polymer as it degrades at 280-500° Celsius. However, some degradation of lignin has been shown to occur at much lower temperature, even as low as 165° Celsius. Toasting temperature has a significant effect on the levels of these compounds. A temperature increase from 175° Celsius to 225° Celsius can increase these compounds 100 fold. Vanillin, guaiacol, and eugenol all increase with time during toasting although eugenol may begin to slowly decrease after the initial increase. In American oak the increase in vanillin during toasting is much more pronounced than in European oak.

Although the polysaccharides cellulose and hemicelluose do not play an import role in flavour unaltered, and are not affected by seasoning, toasting the wood has a dramatic effect. When oak wood is heated, pentoses (the main constituents of hemicelluloses) produce furfural. In contrast, 5-hydroxymethylfurfural and maltol are generated from hexose sugars, a minor constituent of oak wood hemicellulose and mainly found in the more crystalline cellulose. Furfural gives a grainy, biscuity flavour, whilst 5-HMF gives a caramel flavour and maltol gives a candy scent. Toasting temperature has a dramatic effect on the levels of furfural, 5-HMF and maltol in the wood. Like the lignin derived compounds, a temperature increase from 175° Celsius to 225° Celsius can increase these compounds 100 fold. Unlike the lignin derive compounds, furfural, maltol and 5-HMF increase to a maximum at around 30-40 minutes of toasting and then slowly decrease.

Oak lactones give oak is characteristic flavour. Oak lactones are lipids present in green oak, but a glycogongugate precursor is also present. Temperatures greater than 200° Celsius are required to form oak lactones from their precursors. When oak is toasted at 225° Celsius oak lactones are 5-10 times higher than when toasted at 175° Celsius. Oak lactones increases rapidly during toasting (up to 40 mins), after this the levels of oak lactones diminish slowly.

Ellagitannins are also significantly affected by toasting. More than 50% of the tannin content of oak is thermo degraded during toasting. As the levels of Ellagitannins are significantly lower in American oak than in European oak, toasting may leave very little tannin in casks made from the American species.

As we have seen, toasting oak casks significantly alters the chemistry of the wood and prepares the cask to be filled with spirit, but one final stage remains. Next we will consider charring of the casks and how this affects the spirits that mature within them.

By Liam Hirt